weChook Racing: How we use data in the pits

Having covered how Ian uses our measured data whilst out on circuit in the last post (read it here: https://wechook.com/?p=518 ), I’m now going to cover what we can do with it when we’re not racing – be it in the pit lane or once we’re back home.

The first step is getting the information from the car to my laptop. As long as we remember to put it in, the telemetry board will record all measurements to a text file on an SD card, which can then be easily transferred across to a computer. The system also transmits data live wirelessly during a race, but this is of little use when the car goes out of range or behind a tree – pretty much everywhere apart from Merryfield and Dunsfold Park.

For the information to be valuable during the constraints of a race day, all the information has to be pulled together quickly – there’s not a lot of time to make changes in between the end of practice and the start of the race so every second counts. In order to maximise the utility of our data logging, I wrote some code in MATLAB that will read the data files, and generate a report with useful plots and calculations. I’ve uploaded two of these reports, from two different races at Rockingham to the website:

-

Rockingham Heat 2015 (Electric Boogaloo) – https://wechook.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/RockinghamRaceData.pdf

-

International Final Day 1 – Lap Race 2015 (Electric 2galoo) – https://wechook.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/LapRace.pdf

As an aside – I heartily recommend that any aspiring young engineer go out there and get some experience using MATLAB – it is easy to pick up and there is a huge wealth of help and support available online. As a data analysis and visualisation tool it far exceeds Excel, and will make a piece of work look far more professional! I use it extensively at work to perform simulations, automatically generate reports (automating a task that used to take hours keeps my manager very happy) and design control algorithms. From experience, I can also say that if I’d learnt to use it whilst at university, it would have made my dissertation project a whole lot more manageable, due to the Gigabytes of data that I was dealing with from incredibly high resolution measurements of impact data.

Sales pitch over! Once I’ve worked my magic with MATLAB and generated a report we can work out how much current and power we were using at any given point, and how fast we were running the motor. Using this approach with data from a run in practice, we can determine whether we can complete a full race distance at that pace without flattening our batteries (I’ve done plenty of battery testing, so I have a good understanding of how much energy the batteries have available).

Based on the data from the Rockingham heat, we were able to plan our power usage for the Lap Race – we estimated how much shorter it would be than the standard hour and then determined how much more quickly we could discharge the battery. If you look at the two reports linked above, you can see that we drew just under 25Ah from the batteries in both events, but at a higher average rate in the lap race.

Also shown in the reports are traces of throttle position and motor speed. Comparing the throttle trace from the Lap Race to that from the heat earlier in the year, it can be seen that Ian is performing fewer gear changes, and spending less time at part throttle. It can also be seen that motor speed tailed off much more quickly at the end of the Lap Race – we’re putting this down to the fact that we were using our best batteries in the Rockingham heat, but we saved them for the F24+ decider on the International Final weekend.

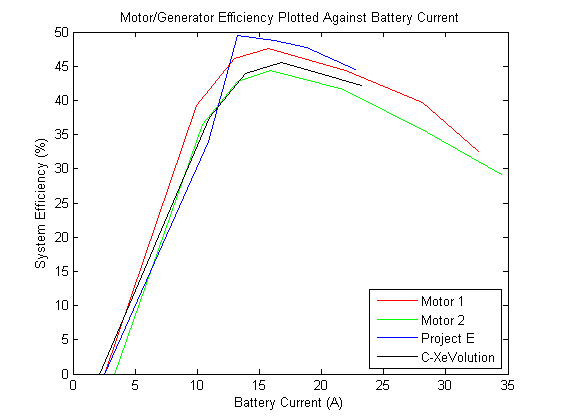

We’re planning to extend our data collection next year to include wheel RPM (from which we can calculate vehicle speed, and determine which gear we were in) as well as motor temperature, to avoid the risk of cooking another one! With this data we plan to be able to run an improved race strategy in the 2016 season – instead of targeting a constant rate of discharge from the batteries, we will be looking at how we can most effectively convert each unit of energy into speed.

Which brings me nicely onto the subject for my next post: Constant Current vs Constant Speed control!